A dialogue

(for Nicolas Boulard)

By Camille Viéville

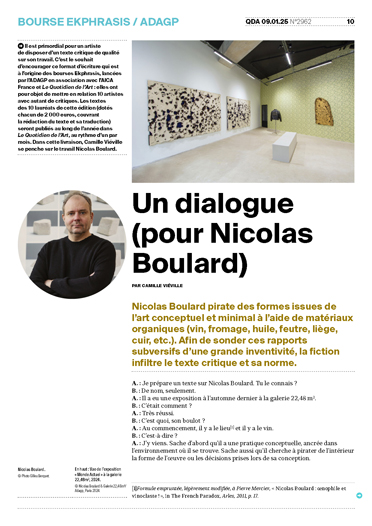

Nicolas Boulard hijacks the forms of conceptual and minimal art by means of organic materials (wine, cheese, oil, felt, cork, leather, etc.). To probe these subversive, highly inventive relationships, fiction infiltrates the critical text and its norms.

A. I’m writing about Nicolas Boulard. Are you familiar with him?

B. Only by name.

A. He had an exhibition at the 22.48m2 Gallery last autumn.

B. How was it?

A. Very successful.

B. What’s his work like?

A. To begin with, there’s the place and then there’s the wine.

B. Namely?

A. I’ll come to that. Firstly, you should know that his practice is conceptual, based in the environment in which he finds himself. You should also know that he tries to hack into the form of the work, or the choices made at the time of its conception from within.

B. Exactly what McKenzie Wark recommends in A Hacker Manifesto, which is hacking to encourage new forms, not always great things, not even good things, but new things.

A. Have you read it?

B. Are you serious? I dropped out of university thanks to that book.

A. ‘Education enchains the mind’…I had no idea that Wark had such an influence on you. So: Boulard hacked art history and his own work. He explores the space of freedom created by the meeting between a norm and a disruptive element. For example, the analogy between the main shapes of cheese and those of Minimal Art (the cube, the cylinder, the pyramid) inspired Specific Cheeses (2010). He designed twelve cheese molds, based on Sol LeWitt’s Twelve Forms Derived from a Cube (1984), and offered them to producers. A dialogue ensued between the artist and each cheesemaker – Boulard calls it a situation.

B. A dialogue? A cheese is a cheese.

A. You’d be mistaken. Changing the mold changes the surface/volume ratio. It affects not only the shape, but also the taste of the cheese, because the shrinkage is different in each mold.

B. What is shrinkage?

- Shrinkage is the loss of matter during the ripening process. Specific Cheeses is the confrontation between a norm – here, the geometry of the producer – and a disruptive element – the geometry of the artist. But there’s more. Cheese, as an organic material, hacks the geometric dogma from within. The soft undermines the hard! We are witnessing a double liberation, from the cheese norm AND from the minimal norm, since cheese, especially soft cheese, continues to mutate after it has been removed from the mold and matured. This is the case with the Specific Cheeses produced by Boulard: the shape varies and is unstable. And as the cheese matures, it collapses…

B. You’re saying that Boulard is a skeptic?

A. It wouldn’t surprise me! But a fruitful skepticism. I’m reminded of another of his works, Mort sur place, a studded leather jacket – ‘Mort sur place’ is an anagram of Marcel Proust. Curious, isn’t it, for a literary star who never left his room? Boulard’s subversion and black humor are resistance. To create is to resist.

B. And vice versa.

A. Indeed, it works both ways! To get back to cheese, the term ‘collapse’ appears a lot in the texts, his own texts, that he publishes under the imprint ‘Éditions de Dés’.

B. A.: ‘A throw of the dice will never abolish chance’.

A. Exactly. And don’t forget that dice are cubes… Remember, at the beginning there is the place. He essentially writes in residence, from a certain place and for a certain time.

B. And what about the wine?

A. Wine, like cheese, is a living thing. It is codified by a standard. Before working with cheese, Boulard was interested in wine. In several projects in the 2000s, he hacked at the explicit and implicit rules of the wine world to the point of absurdity.

B. It’s not clear what you mean. Do you have an example?

A. Yes, of course: Grands Crus de Grand Cru (2004). On the Alsace wine trail, Boulard selected fifty Grands Crus, which he then blended to create what was destined to be the ultimate wine. Something went wrong from the inside. Hijacked in this way, the norm imploded. In 2024, Boulard went back to wine, to the ‘sour wine’ that, according to medieval tradition, could combat black gall. He produced Nuancier (Remède à la mélancolie), one hundred and fifty bottles of vinegar-colored liquid, according to the official rosé wine color chart, which, curiously enough, ranges from violet to lemon yellow.

B. When minimalism becomes pop… And what did he show in the gallery?

A. Boulard often works on the site, the environment, the territory, the edge. For this show he also worked on time, about which, McKenzie Wark, whom we were discussing earlier, wrote – wait, I wrote it down on my phone: ‘A hacker story only knows the present’. Now Boulard has given his exhibition and the accompanying book the title Monde actuel. It’s an anagram of Claude Monet that the artist nails to a leather jacket, as in Mort sur place.

B. What are you talking about? It’s a hundred years since Monet died. We’ve seen more topical things!

A.: You can be so prosaic sometimes. There are artists who will always be relevant, you should know that… Just think of Impression. Soleil levant, Les Meules, Les Cathédrales de Rouen, Les Nymphéas. So many of Monet’s paintings capture an ephemeral moment – a ray of sunlight on the sea, the shadows cast in a field by a straw cone (a minimal form if ever there was one!), and so on. Paradoxically, these are paintings whose subject matter is a transitory moment, but which have spanned the history of modernism and made Monet a star. In the book, Boulard remarks – and I’ve noticed this too: ‘The world today is an organic mechanism that never stops’. Like the fermentation of bread, the mold of Stilton, the noble rot of Sauternes. It goes without saying that one work is a stage, a transition to another. To confront Monet and his myth, he once again provoked a situation. He exchanged with him, brought him up to date. In the gallery, felt tapestries from the Penicillium series (2019) were on display, at once abstract and realistic: a plunge not into a pool of water lilies but into a loaf of Roquefort cheese. There was also Pains (2024), made of walnut-stained plywood. Each slice is monumental, 1.5 meters high. These loaves are hieratic in the manner of Monet’s Cathedrals – with a crumb like a sculpted façade – similar yet different. Then there were two recent landscapes taken from reality, Giverny, earth taken from the Meules field, dried and placed in a frame (it reminds me of a piece from Robert Smithson’s Non-Site series of 1968, made from mud collected in Essen) and above all Soleil levant – Le Havre. Boulard encased water drawn from the port of Le Havre between two panes of glass to create a living tableau in which mist and micro-organisms appear and disappear, depending on to external conditions. This is a triple hacking. He hacks painting as a medium, painting as a flat surface, and he hacks Monet’s landscape, imagining a space in perpetual motion, a space that is constantly up to date.

B. Are you going to talk about all of this in your text?

A. Yes, about all these constantly maturing layers which, when assembled, give rise to new and transient forms…

Text written in 2024 in the context of Ekphrasis grant launched by ADAGP in association with AICA France and Quotidien de l’Art

Published in Quotidien de l’art on January 9th, 2025

translation : Idiomatiques